Man & Light: A Tragedy

Emotive & analytical notes on Anup Singh’s 2017 film, The Song of The Scorpions

SPOILER ALERT: READ ONLY AFTER WATCHING THE FILM!

The Creative Process: To Gaze Within

Art is to society what dreams are to life.

Peter Jordanson

Anup Singh ascribes the genesis of the idea for this film to the aftermath of the Nirbhaya rape in New Delhi, which shocked the nation in 2012. Following the exhausting shooting schedule for Qissa in 2013, Singh recalls a series of nightmares over successive nights, which he then began jotting down aimlessly: images of sand, fire and so on… Over the ensuing four years, these notes went through multiple processes of creation to take the form of The Song of the Scorpions.

In an incredible example of an inside-out self-reflective exploration of a disturbing experience, rather than averting his gaze, Singh confronts his trauma. While most go numb, others choose to project blame or demand accountability. Singh, however, writes his nightmares down and finds courage to weave a story that allows him as well as well as the participants and audiences of his creation to inhabit the lives of both: the raped as well as the perpetrator of this heinous act.

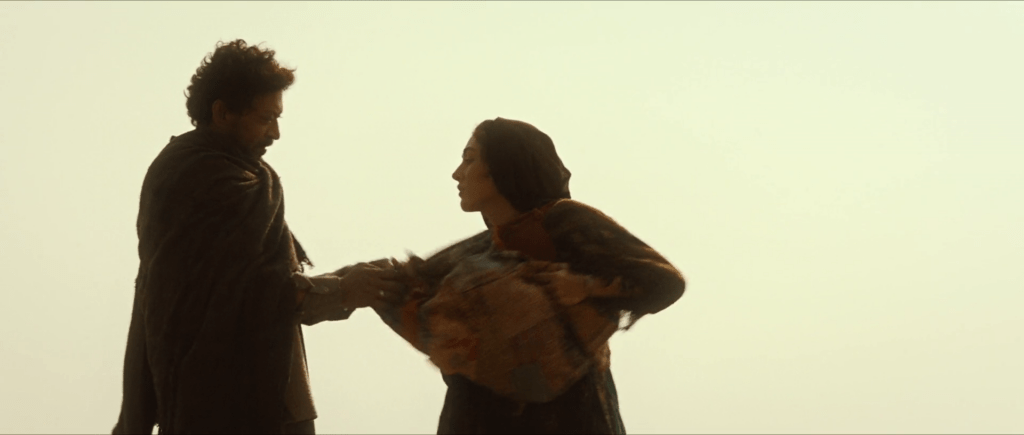

^ the transgression

Perhaps encouraged by Nooran’s taunts, during his penultimate attempt at persuading her, Aadam, tries to assert himself by grabbing her bag hung by her shoulder. In a fallout of this transgression, he is beaten up by passers by. While drawing pleasure in the flirting, Nooran seems prepared neither for Aadam’s impudence, nor for the beating that he gets. She’s woken up from the daze only when one of the women passengers in the Jeep that is driving her home asks her if she’s ok. Nooran suddenly asks for the vehicle to be stopped and gets off to set Aadam’s three camels free, with him unconscious and saddled onto one of them.

In the following sequences of Aadam, we witness him languishing in a disturbed state, seeking firm ground with his sister at her house and also his niece and his daughter. This is also a moment of insight into Aadam’s sense of incompleteness from a broken home. Aggravated by what appears to be his daughter’s lack of interest in him, Aadam fails to find solace and heads out to his friend, Munna, who takes him to a brothel.

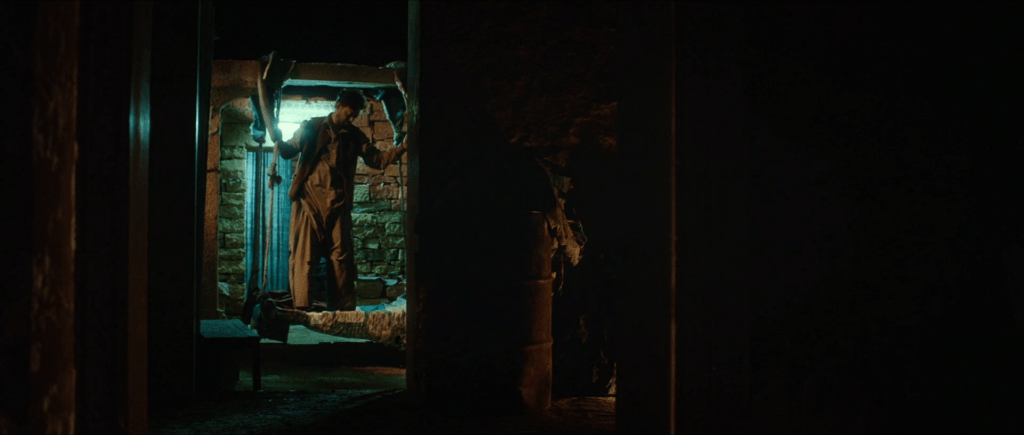

^ the turning point

Sitting on a swing, while Munna is coaxing his beloved, Aadam appears to have sprung up a strategy to manifest his desire of bringing Nooran to him. In a theatrical representation of this turning point, he springs up to turn around and stands up on the swing. Of course, I am connecting the dots in hindsight after the story has revealed itself to me. While experiencing the film, however, at this point in the narrative I am basking in Aadam’s misfortune with no evident turning point in sight. While watching the scenes in a sequence, one only plays along, attempting to make working sense of the string of experiences. The mind, on the other hand, can help rearrange (re-member) the memory that the body holds, with the potential of radically altering the meaning of the experiences. In the five years from Nirbhaya, to the nightmares, to the writing down of the images, to the scripting of the story, to its co-creation with actors and the rest of the production team, the narrative would have undergone numerous layers of creation to acquire a body. The process of editing the film is then akin to the mind rearranging this body of memory.

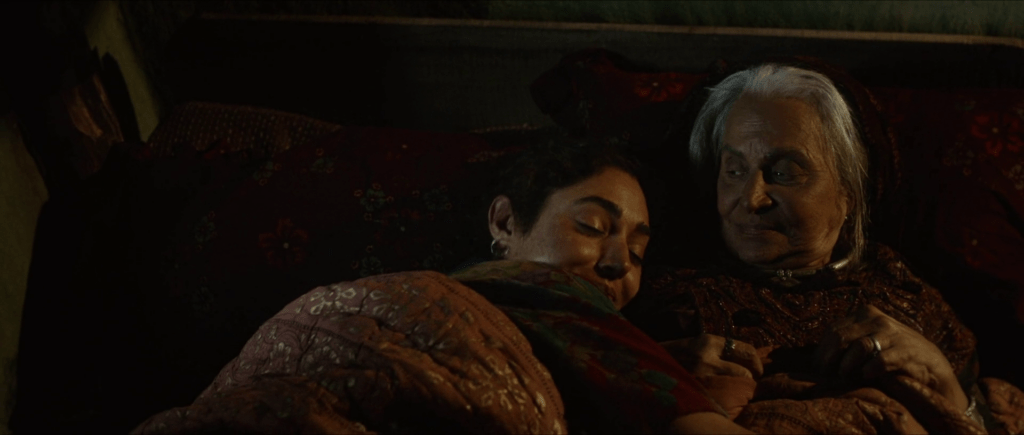

I cannot imagine how much wealth has been shed in the editing process. One of the biggest mysteries is the disappearance of Zubeida – Nooran’s mother. Of course, following the critical disclosure, it is easier to pin this misfortune too on Aadam’s evil scheme. However, this cannot be proved beyond doubt. Woken up by the cold one night during her self-incarceration, Nooran climbs into her bed, re-enacting the playful fight that her mother habitually put up – not allowing Nooran to get into the warmth of the bedding. Zubeida, however, has been missing ever since Nooran returned home after the fateful night. Instead Nooran finds the much coveted quilt under the blanket – a prized possession, which Zubeida had promised would be Nooran’s “without having to ask for” when the latter was ‘ready’.

Besides wringing the viewers’ emotional tapestry, this moment lets loose questions of whether Zubeida left on her own (an earlier moment in the narrative where Nooran’s looking all over for her mother suggests such a possibility)? Or, is Aadam also responsible for her disappearance? Did she intentionally place the quilt under the blankets before leaving or is it just a coincidence? The more one seeks to know, the more entangled do the mind and emotions get. This irreconcilability is appreciable because it corroborates the truth that not everything is explainable.

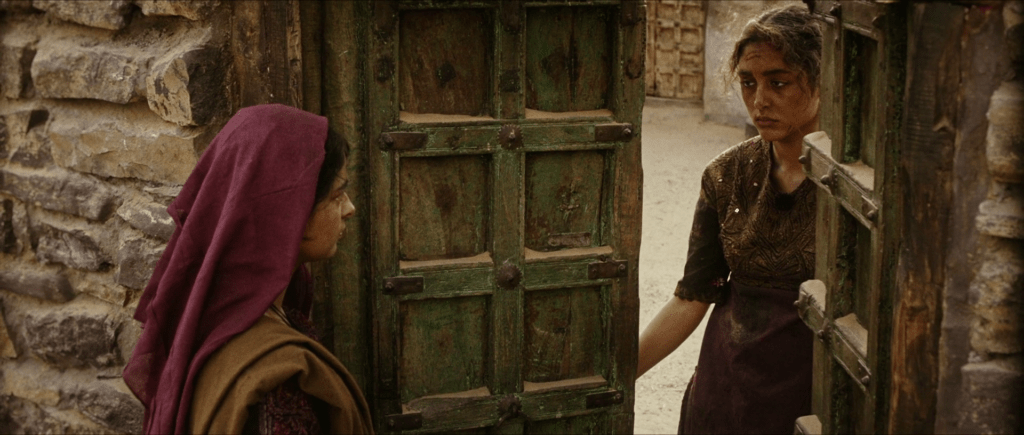

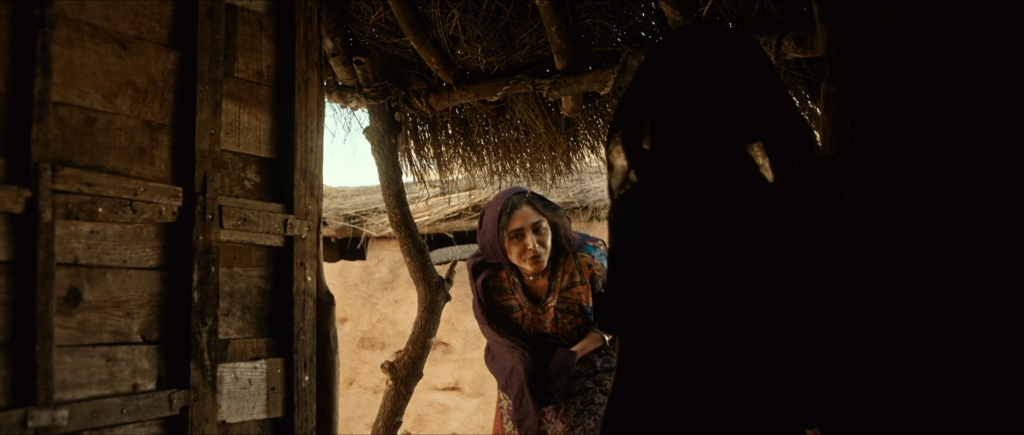

^ the emergence

Finding the orhni is also a turning point for Nooran as the following morning she chooses to emerge from her self-imprisonment. She eats from one of the several packets of food that Amina has been throwing everyday into her yard and opens the door to a waiting Amina who embraces her.

Cinematography: Architectural Frames

^ home

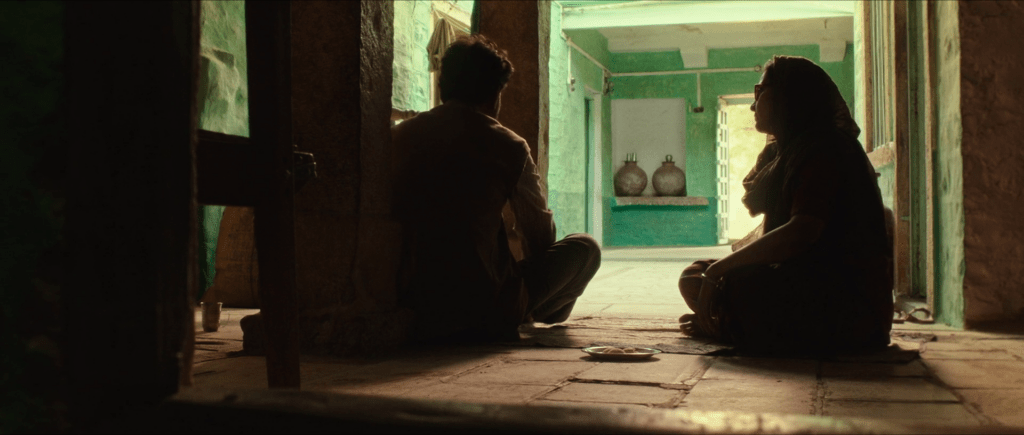

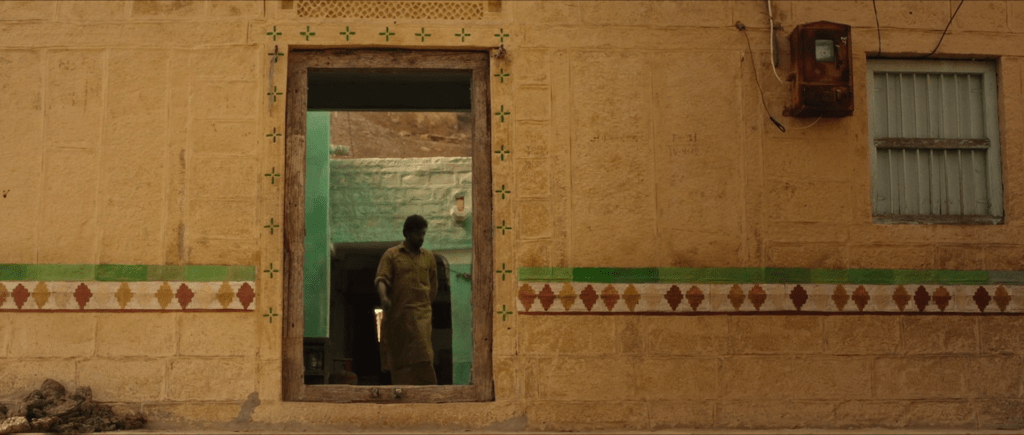

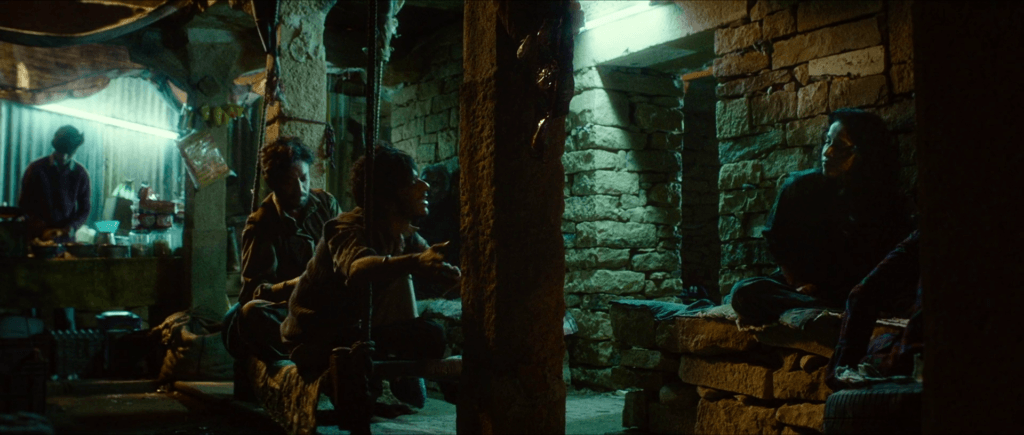

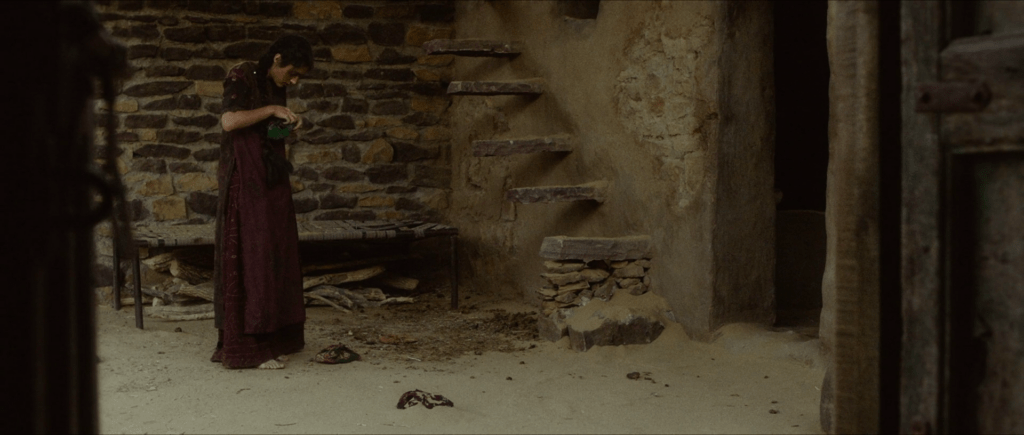

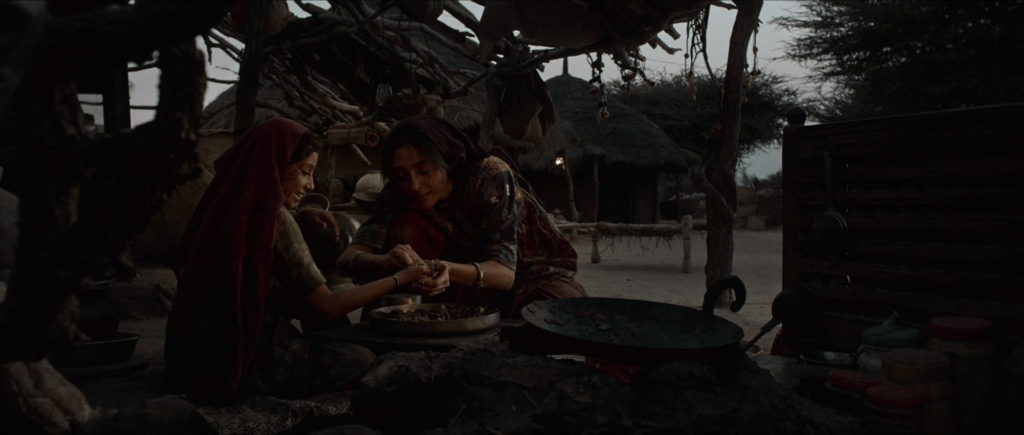

Each frame of this movie is composed with incredible gravitas. While the outdoor shots employ gentle movements through pans, track, zoom, partial orbit etc, the indoor shots significantly employ architecture for framing. The rigorous structure of the frames elicit intimacy or the longing for it – particularly for the two primary characters – providing a strong counterpoint against the voluptuous indifference and ruthlessness of the limitless desert.

^ Nooran on the terrace of her house, with Amina on the steps, looking out at Zubeida singing in the dunes

^ Nooran in the window, as Amina leaves

^ Nooran & Zubeida in the courtyard of a household which they are visiting to cure a new-born

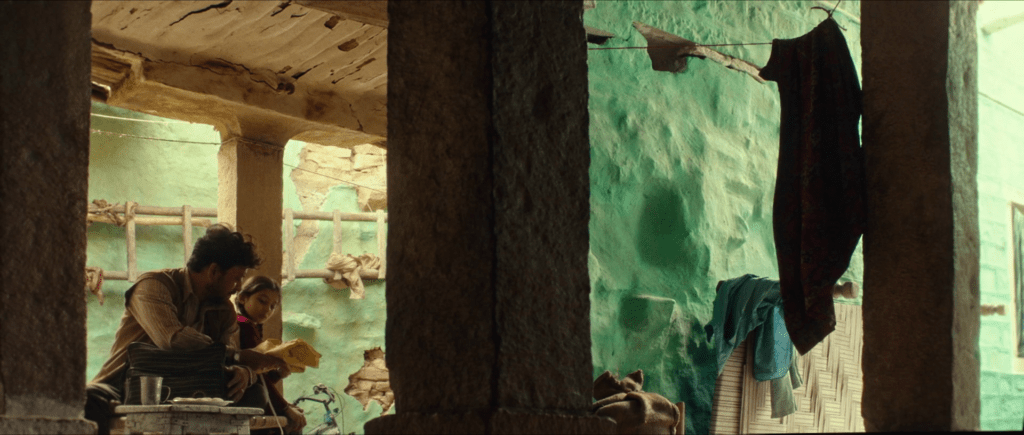

^ Aadam brings clothes for his niece and daughter at his sister’s house

^ Aadam in the courtyard at his sister’s house

^ Aadam looking for his daughter & niece who’ve changed into the new clothes he brought them

^ Aadam realizing that his daughter & niece will not come to play with him

^ Aadam and Munna in the yard of the brothel

^ Nooran waking up in the ruins after the fateful night

^ Nooran in her room at Adam’s house

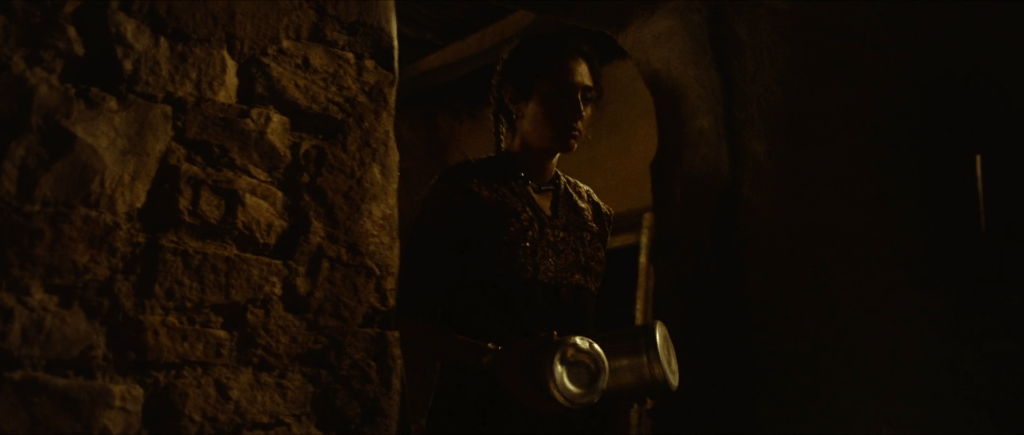

^ Nooran trying to enter Ayesha’s room

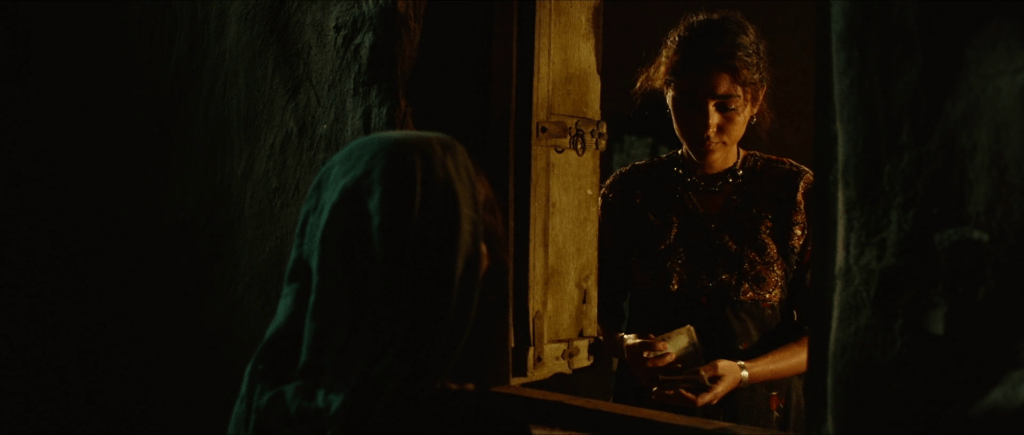

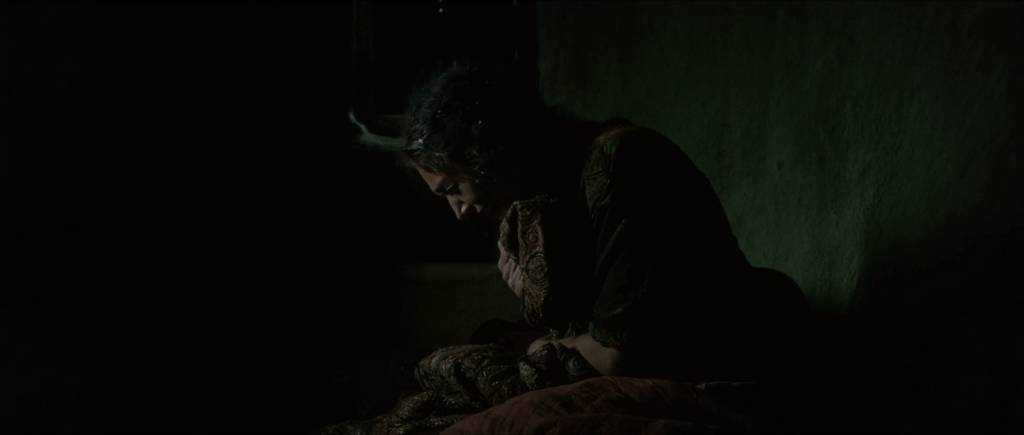

Very many scenes are in deep darkness, accentuating the film’s strategy of incomplete narration, which makes the viewer participate and create the narrative as the story & its characters unfold.

Music: I Can Feel, but there’s no other noise

Notwithstanding the limitations of my direct experience of the narrative’s physical and cultural contexts, I found it difficult to relate the vocals to the visuals: Waheeda Rahman’s singing doesn’t come across to me as the rustic voice of a veteran mendicant; the communal song during Nooran’s pregnancy celebration seem disconnected from the event as the noise and commotion of the gathering have been filtered out; and Bindhumalani’s energetic voice often seems over-enthusiastic. The haunting melody of the bow instruments of Beatrice Thiriet’s background score seem to be derailed by the rhythms of its percussion.

The auditory quality of the music reminds me of the disconnect I felt when listening to the music from a CD accompanying the book, Folk Music & Musical Instruments of Punjab (Pande, Ampin, ‘99). The studio recordings missed out the sense of the outdoors, which is intrinsic to folk traditions.

Bindhulmalani’s seemingly over-enthusiastic singing offers an insight into the near-intimidating aura that Nooran’s beauty casts. Those bewitched by it – Adam and me, because of our deep seated loneliness, grief and longing – are likely to consider her jest with all earnestness and attribute her withdrawal to malafide indifference. I do not wish that Bindhumalani sang with restrained enthusiasm because I understand that engaging in an art that we love instills in us a divine power – turning an otherwise timid Noora formidable. I am only attempting to pay attention to all that which moved me, as much with discomfort as with pleasure. So watching the gap between Bindhumalani’s voice and Nooran’s singing shows me the gap between Nooran’s aura and her vulnerability – smitten by the former, Adam is blind to the latter. The unfortunate and violent fall out of his proposal to Nooran and his subsequent isolation makes Adam scheme an evil plan to break her by taking away her sense of self worth, and presenting himself, very patiently, as her savior. This is an incredibly human mess.

While the songs are deeply rooted within the story, its characters and their contexts, they don’t make for easy listening. Carrying Madan Gopal Singh’s distinct signature, the powerful compositions are further accentuated by their bare renderings – no instrumentation or arrangement; just pure vocals – carrying melancholy along with the anticipation of joy. Despite their power, or perhaps because of it, I found them quite often challenging the notions of melody. This, of course, is a conscious creative trajectory chosen by MGS, who believes that “music is not a mere collection of pleasant sounds.”

Motifs: Seeking & Holding

I noticed a few motifs in the film – recurrent actions by the protagonist and other characters – occurring twice; seemingly as a suggestion of a cycle with different points of return. The entire sequence of Nooran’s walk back home through the village with Amina to her house in the outskirts, entering her courtyard and looking around for Zubeida happens twice. It’s playful the first time, while is saturated with stigma, shame and fear the second time. Nooran is also in the ruins twice: the first time, unintentionally, she’s found there following the fateful night and the second time she heads there after emerging from her self-incarceration. One of the repeated occurrences is of seeking love in the desert: on two occasions, as mentioned earlier, Nooran looks for her mother in the dunes surrounding their home. She’s unsuccessful on the second occasion. In a fascinating symmetry later on in the story, Adam too goes out seeking Nooran in the dunes near their house twice, and, again, he is unsuccessful in his second attempt.

I find another motif rather poignant and subtle: frames of Nooran holding on to a thing or person endearingly.

^ Nooran carrying empty boxes of grain to Zubeida to convey that they need the money

^ Zubeida instructs Amina to distribute the money earned by Nooran among the poor, but she brings it back to Nooran

^ Nooran hugging Amma (Zubeida) in the bed after practicing to sing in the cold night outside

^ Nooran finds the coveted Orhni (which Amma had promised her when she’s ready) under the blanket

^ Stepping out of her self-incarceration, Nooran picks up a packet of food thrown into her yard by Amina

^ Teaching Ayesha to make laddu

^ Gently strokes her pregnant belly, while singing and perhaps remembering her lost self and her mother

^ Picks out a scorpion from a boxful to hold it in the hollow of her closed palms and get bitten by it

Violence: to Identify as Separate

As I began contemplating and writing about this beautiful film, I couldn’t help but remember Thic Nhat Hahn’s proverbial observation: “To love without knowing how to love wounds the person we love.”

Nooran: “I didn’t get you beaten up!”

Aadam: “You didn’t stop them either…”

Following his violation at the hands of strangers, while his beloved stood as a mere spectator, Aadam is bitterly disappointed at such a turn to his year-long pursuit of Nooran. He schemes and perseveres with incredible patience. He gets Nooran violated by his friend, Munna and remains out of sight till Nooran emerges from her self-incarceration and heads out to find her missing mother. Particularly after their wedding, he is very tender with Nooran and never shows impatience in consummating their marriage. On one instance when Nooran has walked out of the house to sit by herself amongst the dunes, Aadam follows her to give her a blanket and, handing her a knife, tells her, “If I ever touch you without your consent, keep this…”

Upon learning of Aadam’s evil scheme from a dying Munna, Nooran’s immediate reaction is to pack-up and leave; however, chancing yet again upon the quilted orhni, she schemes her vengeance instead. In a very intriguing move, as Aadam comes looking for her, she meets him intimately and the husband and wife consummate in the desert amidst sand dunes and the evening sun.

Singh is piercing through the easily acceptable definitions of evident violence and showing us the implicit violence that we inflict in the name of love. We are capable of ruthless manipulation & deception, most of which could be set off sub-consciously – in our relationships and against ourselves – as part of our deep-seated patterns. Most of it is also carried out to prevent – at any cost – our abandonment. How ironic is it that our actions of self-preservation – to usurp, to separate from others and to even identify as an individual – is rooted in our need for community or ‘the other’.

Turning the nuanced narrative from what appears in the beginning to be social drama into a fairy tale and then into a deeply insightful human tragedy, The Song of the Scorpions is the story of man’s enchantment with the light of beauty and divinity. A tragedy of identifying the light as being separate from and outside of the self, the desire to possess it and the fall out of this pursuit of possession.

I find it apt to close this series of thoughts and feelings triggered by this wonderful movie with a part of Thic Nhat Hahn’s poem (Peace Every Step, Rider, 1995),

Please Call Me By My True Names

I am the mayfly metamorphosing on the surface of the river,

and I am the bird which, when spring comes, arrives in time to eat the mayfly.

I am the frog swimming happily in the clear pond,

and I am also the grass-snake who, approaching in silence, feeds itself on the frog.

I am the child in Uganda, all skin and bones, my legs as thin as bamboo sticks,

and I am the arms trader who sells weapons to Uganda.

I am the twelve-year-old girl, refugee on a small boat, who throws herself to the ocean after being raped by a sea pirate

and I am the pirate, my heart not yet capable of seeing and loving.

I am a member of the politburo, with plenty of power in my hands,

and I am the man who has to pay his “debt of blood” to my people,

dying slowly in a forced labor camp.

My joy is like spring, so warm it makes flowers bloom in all walks of life.

My pain is like a river of tears, so full it fills the four oceans.

Please call me by my true names,

so I can hear all the cries and laughs at once,

so I can see that my joy and pain are one.

Please call me by my true names,

so I can wake up,

and so the door of my heart can be left open,

the door of my compassion

****************************

malkum

malkum