Solitude, Sensuousness & Spirituality

Peter Zumthor’s Bruder Klaus Field Chapel

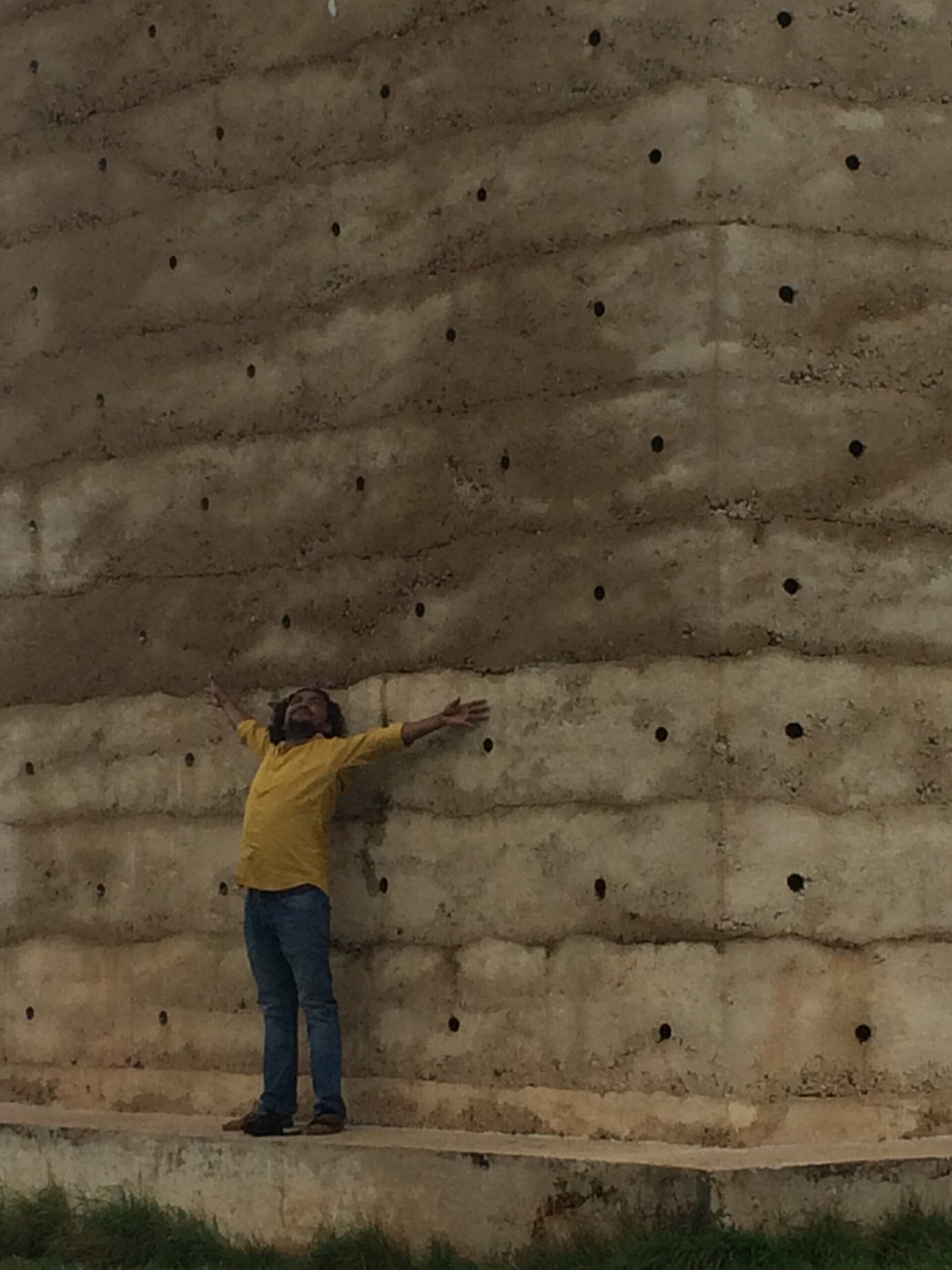

As we approach the chapel, which is a long walk amidst rolling fields, not only does the tower stand as the lone identifiable building in sight for a large expanse around, but is also alien in form and material compared to the structures and settlements that one has passed behind. Evidently, the chapel – in its solitude contrasting the clusters of trees in sight – anchors the swelling ground. The anchor, however, isn’t static. The stark tower with indisputably vertical edges defies clear definition of its form. The proportions of the extruded polygon change as the observer’s position changes. The prism appears most slender when facing the narrowest facade up-front – barely suggesting the third dimension as only two of its vertical facets are visible. From the rear, on the other hand, the chapel appears stout, disclosing three of its faces. In the definite verticality of its edges and the relentless challenge to the comprehension of the whole, Zumthor’s Bruder Klaus Chapel is comparable to Corbusier’s Chapel at Ronchamp. Zumthor’s expression, however, is singular, unlike the plurality of elements at Notre Dame du Haut, and perhaps more enigmatic for this austerity. The triangular entrance door on the narrowest face towards the south-east further confounds one about the ultimate form of the structure. The door, which covers one of the only two symmetrical elements in the architecture of the chapel, hints at the sectional profile one is about to experience inside.

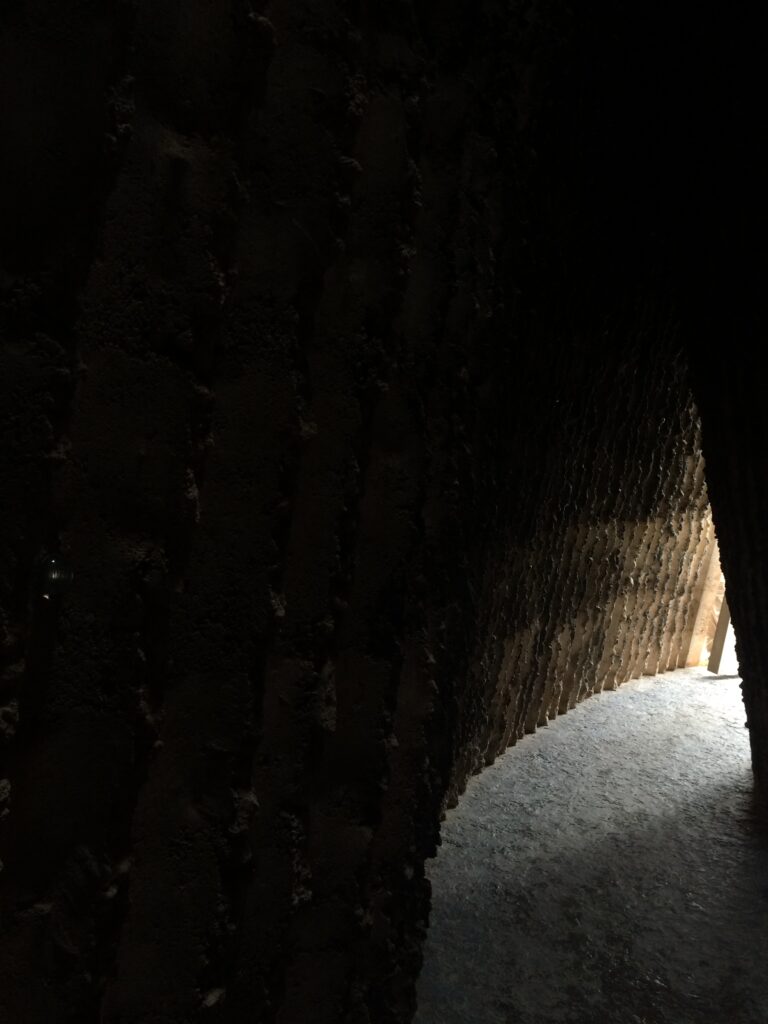

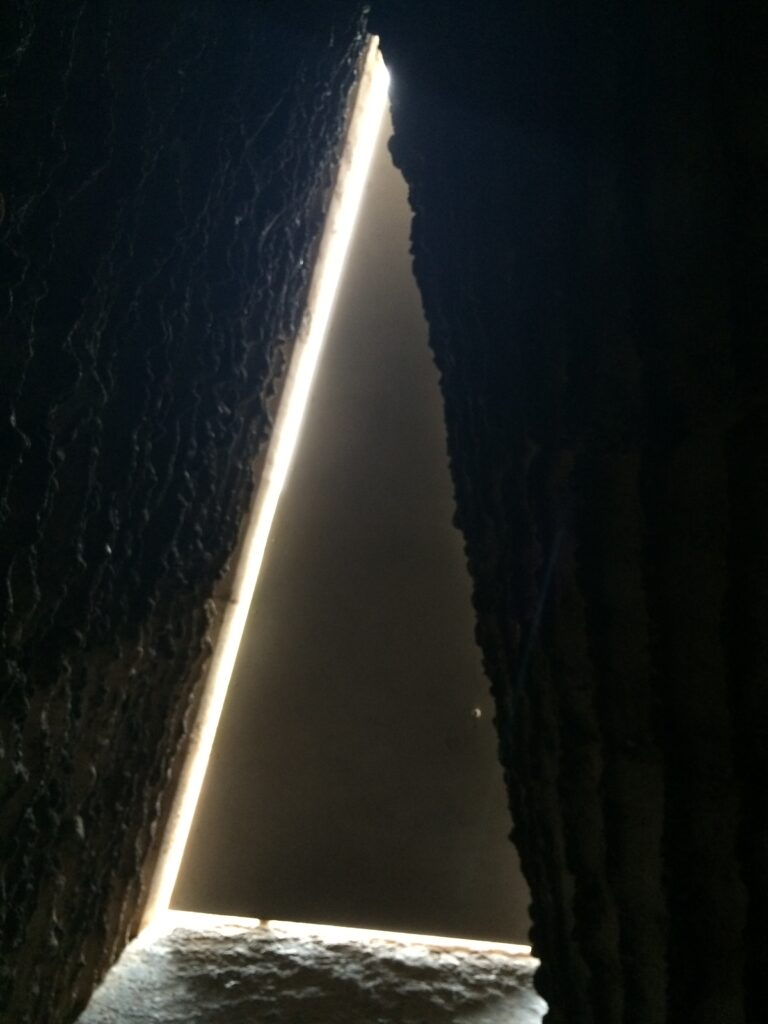

Wondrous dark space gazes back as one stands at the threshold with the opened door. Broken-edged striations of light and shadow on the walls forming the doorway, tapering into a ridge overhead, provide some measure to the depth to be traversed. As one moves inward, the corridor curves gently to arrive at the womb: an organic bulbous space barely enough for a handful of people. The striated looping wall hurtles upward, tapering to culminate high above into a droplet shaped oculus: the other symmetrical element of the architecture. The oculus is unprotected, and the floor below retains a puddle following rain. The dark womb is a space of intimacy with oneself and with the elements.

The spatiality and articulation of the inside of the chapel are not only disjunct from its form but also contradict it. Each of the outer facets is orthogonal and flat, they are bright with the relative smoothness of cement concrete, acquire a yellow glow when moistened by rain owing to the properties of the mud content and carry traces of horizontal layering of the concrete. The opening for entrance through the severe geometrical edifice is a clean cut isosceles triangle. In contrast to the planar ‘building’ outside, the inside is carved out – a dark, charred, cave seeking primordial intimacy. The deep, rugged but regular gashes, creating shadows, are an impression the act of scoring and emphasize the mystery. The organically symmetrical oculus, as against the precise entrance opening, retains its coarse profile of inverted fluting. The space, like the form, is singular as well; however, it’s an amorphous flow from the doorway to the oculus settle – unfaceted, cornerless.

The chapel is asymmetrical within and without – except for the two openings at its ends. It is consistent in its singularity in form and oneness in space, though each is distinct and disjunct from the other. We may identify facets on the edifice or volumes with the space, but these are only identifiable parts, not separable. It is tremendously fascinating that this unity and disjunction are brought together through a single material – concrete: plastic but rock-solid, a composite mix yet homogenous. Hundred-and-twelve logs are assembled to tent up as the entrance passage and the twelve meter high spire – a form, in all likelihood, identifiable as a shrine, which is then buried in layer after layer of rammed concrete. The twenty-four layers take as many days to cast and, once settled, the wooden tent inside burns for days, as it is set on fire to only leave behind charred gashes and space as trace. This remarkable process presents inversions at multiple levels:

- The form of the spire is obliterated to retain only the space

- Concrete’s plasticity, usually, lends it to rampant use in passive forms – unrelated to location, use and inhabitation, like a frame; here, however, the consolidation of an organic spatiality makes it unique and specific – the process turns the formwork into space

- The contradiction in space and form makes the load-bearing structure top-heavy – perhaps that’s the reason for the plinth protruding from three of tower’s longer sides, acting as counter load

- The holes in the concrete wall – perhaps intended for tying the inner and outer shuttering – were to bring the breeze into the sanctum sanctorum; their plugging with glass bulbs is, apparently, an afterthought; nevertheless, as one peeps through a droplet from within, the world outside appears inverted

The transitory form in perception, the mud in the concrete and its animated response to the weather, the stains on the outer surface and the folds within – akin to skin, the darkness inside accentuating the senses, the charred wall evoking smell, the light and shadow, the sound of the wind and the moisture, all converge in this pilgrimage of heightened sensuousness full of anticipation and surprise, leading to wonder and awe of our ‘being’. When one looks up at the oculus on a bright day, the streaks of light and shadow radiating from the brilliance and the sprinkle of little bulbs of light create the impression of what a star burst might look like – the origin of all.

Annexure 02 May 2024

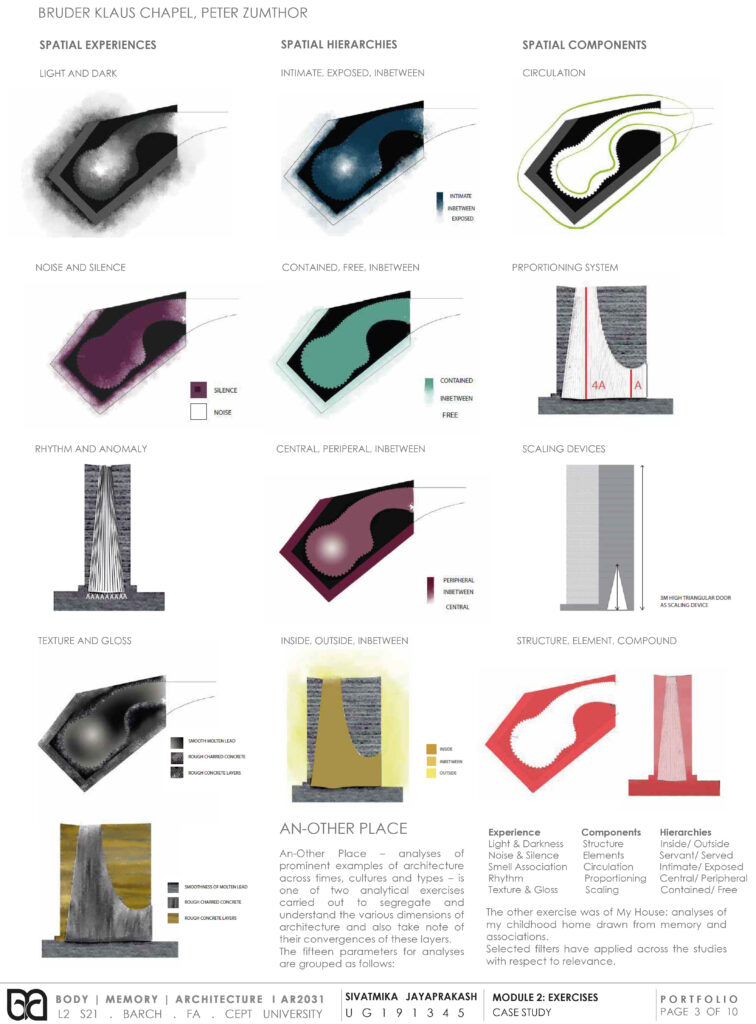

In my architecture & Spatial Design studios, I offer an analytical framework that makes students pay attention to the spatial experience, hierarchy & components of an architectural case-study as well as their childhood homes. Experience is further categorised into the study of Light, Noise, Rhythm & Texture. The opposite of each of the characteristics are also observed. Spatial Hierarchies include qualities of Intimacies & Exposure, Containment & Freedom, Central & Peripheral, and Inside & Outside. The in-betweens of each of the opposing qualities are also observed. Spatial Components comprise of Circulation, Proportioning System, Scaling Devices and Structure, Elements & Compounds. While I believe this to be a rather comprehensive framework for elementary analysis of a building, the Bruder Klaus Chapel presents a formidable challenge to not only this framework, but perhaps to an analysis of any kind.

During the Spring iteration of my studio Body | Memory | Architecture, which I conducted through 2021 at the Faculty of Architecture, CEPT University, Ahmedabad with Sukhmani Brar, one of the students – Sivatmika Jayaprakash – showed the courage of analysing Zumthor’s enigmatic chapel.

The chapel is a small singular entity built in a unique organic way without the assembly of parts; therefore, it offers almost nothing in terms of studying Components (structure, elements & compounds, proportioning system, circulation). It is so compact that in terms of Hierarchies that anything other than the actual center (which too perhaps depends on the position of the sun in the sky) everywhere else is periphery. One is either contained & intimate inside or exposed & free outside. This work of architecture exposes the limitation of my analytical framework, which is perhaps suitable for building with layers & larger in size. Nonetheless, in spite of its compact size, or perhaps because of it, the chapel is dense and intense in the experiences that it offer. It is a space within a monolith to find in solitude the rhythm of the self resonating with the cosmos.

malkum

malkum